Film Extracts – Transcripts

Piece Tin

An’ your, your, your, eh…your piece, come piece, [Chuckles] it was shaped like a plain breid, it was shaped like a Scottish loaf! An’ you hed a tin, an’ your mum fillt, your mother filled it wi’ tea, an’ your sugar an’ put a soak [sock], put it in a [laughing] soak [sock] tae keep the water off! [laughing] An’ it would ay end up cauld! [Laughing]

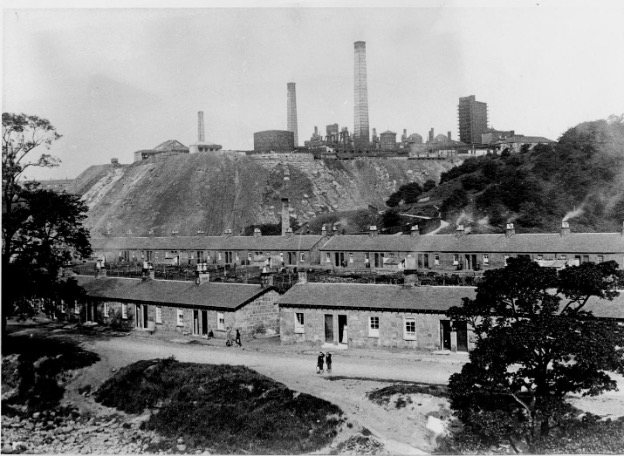

Pugs and Washing

We’d put the washing oot on the line, all right doon the row. Lovely, white nappies, right doon the row. An’ then the tug would come along the Waterside, do you ken what the tug is?

It was a shuttle train.

An’ it would come along the line an’ stop just at the back o’ the pit an’ I don’t know what the hell it blew but they blew something an’ w’or washin’ was all spotted wi’ soot!

So, we’d t’ tak it all in an’ wash it again! We kicked up hell about that but it did nae work! Naebody listened.

So, we’d just t’ keep going. Bring, put the worst o’ them in, back into the washin’. [Chuckles] Shouted our faces off fer weeks but nah, naebody listened!

The Spoot or Pump

You see, down at the end of the rows, that’s where the water was and it wasn’t even a tap that you turned on, it was a pump! An’ the women had to get their pails, two at a time, right, up there, pump the water into the pails and carry them back up to the house, two at a time, and back down with another two so it took them a while to stock up the water for the needs for the day! I mean, they’d have to go back down later and get some more fresh water but this water was fed from the hillside. It was, sort a, routed down wi’ a pipe to this pump, and the women had to pump it there to get the water. So, it was only cold water, carried up to the house and that’s where they had t’ use this stone sink. […]

out the back door an’ there was a, a trough that went down. It was made of bricks, I can remember that. Er, and you threw your dirty water into that an’ the rainwater flushed it away so, that’s what happened to your dirty water. Aye.

Wash House

Now, the procedure for the washhouse is, there’s a huge cast bowl and the housewife whose turn it is to do the washing, goes round about four o’ clock in the morning and light the fire so the water in this cast iron tub is going to be hot enough to do her washing. It doesn’t matter what the weather’s like, if it’s your turn for the washing you’ve got to do it this week or you can’t do it until next week! So, these were communal. So, you can see that this is a community…

Having a Baby

Aye, apparently, when I was born, er, the women went to their bed for ten days to a fortnight and that was their, sort of, ante natal care and their neighbours came in and helped an’ the nurse was coming up every day to see that things were OK an’ Mrs McBride, that stayed at the other side, had came in an’ my Mum never liked margarine, she liked butter. She hated margarine an’ would nae eat it kinda style! If she’d nothing else, she would just spread it on so thin that you didnae get the taste. But she loved butter and she would have it as thick as she could but it was on ration, you see? Now Mrs McBride had a bigger family and she’d more butter in the house so she came in with a wee tray an’ a nice wee cloth over it an’ a cup o’ tea and a plate wi’ just bread and butter but nice thick butter! “Here you are, Sadie, I thought you would like that!” And my Mum says, “Oh, my God, that’s lovely! Oh, that’s good!” She said, “I never enjoyed anything as much that day!” It was just that nice that somebody came in wi’ that, something that she liked. An’ she was so happy! An’ she talked about that afterwards. I mean, that was a nice thing.’

Pit Baths

Pennyvennie. Everybody had, you’d that many different kind of folk an’ na, comedians, different natures an’ it was really a great pit t’ work in! We were all, you knew everybody in it! An’ you [Chuckles] [Pause] You’d mebbe be, when you come up frae the pit, as I say, you just put a towel roond aboot you an’ went into the shower an’ somebody would say t’ you, “Harry, will you wash ma back?” Well, as I say, the fella that worked on the coalface, they were, like, black lead so they always had tae get somebody tae wash their back, but you’d step oot an’ somebody would hae a hose at you! [Laughs along with AM] But the, no, they were a great bunch o’ men! I [Pause], oh…I get emotional when I’m talking aboot some o’ them

Washing At Home

Att that time at the pits, there was nae baths or anything at the pits, the men had t’ come home an’ wash when they come home. An’, er, an’ the boiler was always on for hot water for them when they come home.

Women’s Lives in the Villages

- Themanwastheheado’thefamilyan’thewife,magrannyferinstance,who came from Lanarkshire, a mining place, an’, er, they’d no life whatsoever! All they had, ma memories, were all they had was – cooking; washing…dirty pit clothes; drying them round the fire an’ the place was steamin’, of course, because they came hame very wet sometimes; an’ having kids! An’ that’s, that’s ma assumption.

- Och,therewerenaesocialsuponthe‘hill!They’retoobusyworkin’!Therelife was a trudge. ‘Cause it was the, trying to keep the house clean wi’ the coal fires an’ trying t’ keep a washing goin’ an’ make food – their life was really nothing.

Women Supporting Each Other

An’ they always helped one another out. I mean, they would say “Mrs so-and-so up there, you ken, he’s not at his work yet, no, it’s a shame!” And they were all making pancakes and stuff and handing them in. They always helped their neighbours because they knew what the position was and it could happen to them just the same. They were very good at looking after one another.

Kindness

But my mother said the kindness in the rows at that time when a baby, if somebody was in labour. One neighbour would be making a pot o’ soup! Another un would take the weans in! Er, you know, they all helped!

Pitch and Toss

YM: what kind of things did the men do when they weren’t working?

When they weren’t working. Oh, they would go to the pub and have a drink an’…play pitch and toss! That’s a, do you ken what that is?

YM: What is that?

Pitch and toss?

YM: Aye.

Throw a penny or that up in the air an’ say heads or tails when it hits the ground. YM: Ah, right.

Right? [all laugh] YM: Aye!

That’s pitch and toss.

Pigeons or the Doos

The days when they had pigeon racing on the ‘hill [pause] and, I don’t know if you know, understand pigeon racing. You don’t actually race pigeons at all! You put a little, rubber ring onto its leg. [Pause] When the pigeon comes home, to its own loft, you take that rubber ring off off its leg and it goes into a thing a bit like a thimble and then it goes into a timing clock, you turn the handle and it stamps the time and it’s only when that handle is stamped, has your pigeon arrived. [Pause] Now, on the ‘hill, they had only one pigeon clock for the seventeen or eighteen members who raced pigeons so, all the wee boys who could run fast, were given a thruppence or something by the pigeon fanciers so that when they timed a pigeon, they gave the ring to the wee boy, who would run like stink to wherever the clock was kept and it was, it was then timed in! So, even if you knew nothing about pigeons or cared nothing, for that thruppence you were prepared to run your, your hardest on the ‘hill t’, t’ time in the pigeons.

Darconner Footage – leaving the villages

So, so, the, killing the pit killed the village really an’, you know, the village population just steadily declined an’, you know, row after row of houses got demolished as people moved away; and the hardcore were left, er, to be moved in 1954. And they moved us all to one street in Glenbuck, in Muirkirk.

Life in Lethanhill

- Aye,well,Iwashappy.Everyonewashealthy.Abitcarewornattimesbutitwas a guid life. I mean, everybody knew everybody. And everybody helped everybody. But, eh, if one was in bother, well, trou, some trouble or other an’ the rest o’ them would, like, go to help. A very close community.

- Well,asIsay,itwasahappylifeupthere.Everybody,asIsaid,everybodytook part in everything an’, wi everything that was goin’ on an’ we used t’ have sports and that for the young folk and in the summertime, there were many different things. An’ there was a village hall. There was a village hall up by where the war memorial is. Going up past that, there was a village hall up there. They used t’ have dances an’ that in there sometimes for the, all the families an’ all that went t’ them, to them an’ that. […]It was a great place to stay. Lethanhill and Burnfoothill. Everybody helped one another