The mining villages built by mining companies throughout Scotland in the mid-nineteenth century were all remarkably similar in design. The workers houses were built in rows of varying lengths. The longest row in East Ayrshire, possibly Scotland, being the Common Row near Commondyke which had 96 houses contained in one continuous stretch. The walls were largely of local stone or brick and the roofs were for the most part slate. Though according to the 1913 Miners’ Row Report, by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown, some roofs were covered with a tar cloth, such as Rows 3,4,5 and 6 at Cronberry near Lugar, owned by Baird and Co.1

A miner’s house was very basic accommodation. They were all largely built with no running water, no w.c, no drainage and no external paving. By the 1920s. most of our villages had an electric light in each room.

Here Sam Purdie describes the houses in village of Glenbuck (pictured above):

Glenbuck itself was, being so small, it was a complete community. Everybody knew everybody else! First of all, Glenbuck was primitive – there was no electricity, there was no gas, so all cooking was done on the fire and this huge grate formed the mains hub of the living room because miners lived in rows, comprising two apartments and sometimes ten of a family in these two rooms.

Interview with Sam Purdie (to listen click here)

Andrew Sim, whose father was the village joiner employed by the company, contrasts his parents’ new home in Doonbank in 1954 to their house in Lethanhill:

An upstairs house in a block of six houses containing living room, two bedrooms, kitchen and bathroom – what a difference from the home of my birth – which contained a large living room, containing two inset beds, a separate bedroom, mainly kept for visitors, a kitchen, wash-house and coal-house – no w.c. It was housed in a ‘privy’ up at the top of the garden 25 yards away. We had a cold water supply only. All hot water had to be heated. The kettle was almost always on the stove – a solid fuel coal burner. Our family were lucky. My father put in a cold water supply to prevent my family having to bring their water to the house by buckets from the “spoot” about 25 yards up the back road outside the Harvey House.

Quoted from unpublished autobiography of Andrew Sim donated to Lost Villages Project.

Inside the house

Inside the miner’s house, we find one or two rooms with a scullery or kitchen to the rear. Often families lived in one room with beds inset into the walls. Some had a pull out beds underneath, referred to as hurly beds, that were stored away during the day. The bed area was curtained off during the day. Alice Wallace describes the house she grew up in Benquhat in the late 1940s:

It was one room and a kitchen. And that room was the living room, the bedroom, the dining room, everything! So, you had your three-piece suite set round the fire and there was a table and chairs an’ one wall was actually taken up wi’ two recess beds. Now, if you know what that is, Yvonne, they’re built into the wall, right. A partition up between them, quite a strong one. I mean, I suppose it would maybe be a brick partition, to separate these two beds. Now, the beds were actually built in. They were quite high. The framework was built in. And my Mum and Dad were in one bed and Robert, Billy and myself were in the other and in below these beds, as I say, they were high, there was storage down below [chuckles] and there was what they called hurly beds down below! And these were hurled out and hurled back in as they were used. Well, we didnae have a need for the beds really but there was loads of storage for everything else – all the toys and everything that was lying about was just thrown in there and out of sight. And there was curtains that shut these recesses off through the day and the place looked lovely and tidy but in there, there would probably be quite a lot of clutter but it was out of sight! Aye!

Here we can see most families were living, and often sleeping, in the one room. Even in the case of the Sims who had a separate bedroom, it’s noted that that was for visitors. In the 1913 report, some families rented two houses and knocked them through to have more space.

Kitchen/Scullery

To the rear of the houses was a small kitchen or scullery. It had a sink and often a boiler. Alex Kirk was born in Lethanhill and lived in the Polnessan Row in Burnfoothill until he was about 7 years old, recalled the importance of the boiler for the men coming home from a day in the mines when there was no pithead baths.

There was a wee, there was a wee kitchen at the back, kind of, at the back o’ the house. Wi’ a boiler an’ everything in it. A big boiler for, at that time at the pits, there was nae baths or anything at the pits, the men had t’ come home an’ wash when they come home. […] They came in the back door, aye. An’, er, an’ the boiler was always on for hot water for them when they come home.

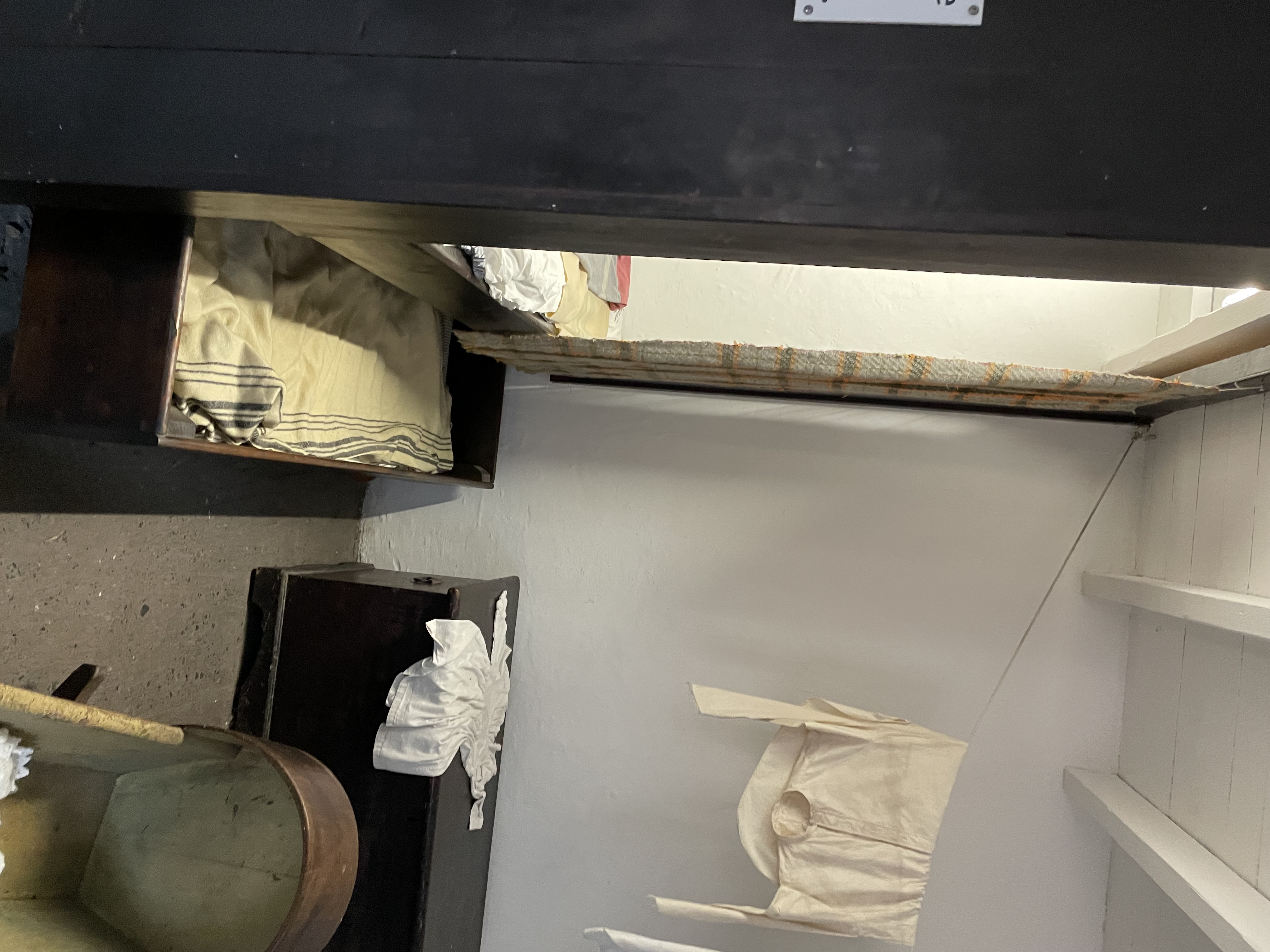

IMAGE: Remains of a kitchen in Lethanhill, 2022

Not all families were are fortunate as the Sims to have a cold water supply. With no running water in the most of these houses, the task of collecting water from the spot involved quite an effort on the part of the village women. Here Alice Wallace describes the work her mother had to do to ensure the family had enough water for the day.

Aye, well, my mother would bring water in. You see, down at the end of the rows, that’s where the water was and it wasn’t even a tap that you turned on, it was a pump! An’ the women had to get their pails, two at a time, right, up there, pump the water into the pails and carry them back up to the house, two at a time, and back down with another two so it took them a while to stock up the water for the needs for the day! I mean, they’d have to go back down later and get some more fresh water but this water was fed from the hillside. It was, sort a, routed down wi’ a pipe to this pump, and the women had to pump it there to get the water. So, it was only cold water, carried up to the house and that’s where they had t’ use this stone sink. So, they would heat the water up for getting washed an’ doing their dishes and things like that. But when they were … by with the water, they could nae pull out a plug and let it run away, there was no plumbing! They had t’ bail this water back into a pail and back out the back door an’ there was a, a trough that went down. It was made of bricks, I can remember that. Er, and you threw your dirty water into that an’ the rainwater flushed it away so, that’s what happened to your dirty water. Aye.